What is melancholy in the 21st Century?

[ad_1]

Features correspondent

Alamy

AlamyIn the second of our Art of Feeling series, Kelly Grovier explores how views of despondency have changed over time – and what role it can play in combating despair.

Can paintings and drawings help us cope with sadness? The history of art believes they can. From Albrecht Dürer’s 16th-Century woodcut of a sulking angel to a protest mural created in London earlier this year that has been attributed to Banksy (proclaiming ‘From this moment despair ends and tactics begin’), there exists a secret tradition of images that presents melancholy not merely as a malady one suffers but a cryptic puzzle that can worry us out of worry.

Like sudoku for the soul, such retinal riddles as Lucas Cranach the Elder’s painting Melancholia (1532); Artemisia Gentileschi’s Mary Magdalene as Melancholy (1622-25), and Giorgio De Chirico’s desolate dreamscape Melancholy and Mystery of the Street (1914) rescue us from the despondency we may share with them by busying our brains. These works spring from the same instinct that provoked the 17th-Century English scholar Robert Burton, author of the influential 1621 tome on depression, The Anatomy of Melancholy, to insist that “there is no greater cause of melancholy than idleness, no greater cure than business”. What sort of business? “Melancholy can be overcome,” Burton concluded, “only by melancholy”.

Getty Images

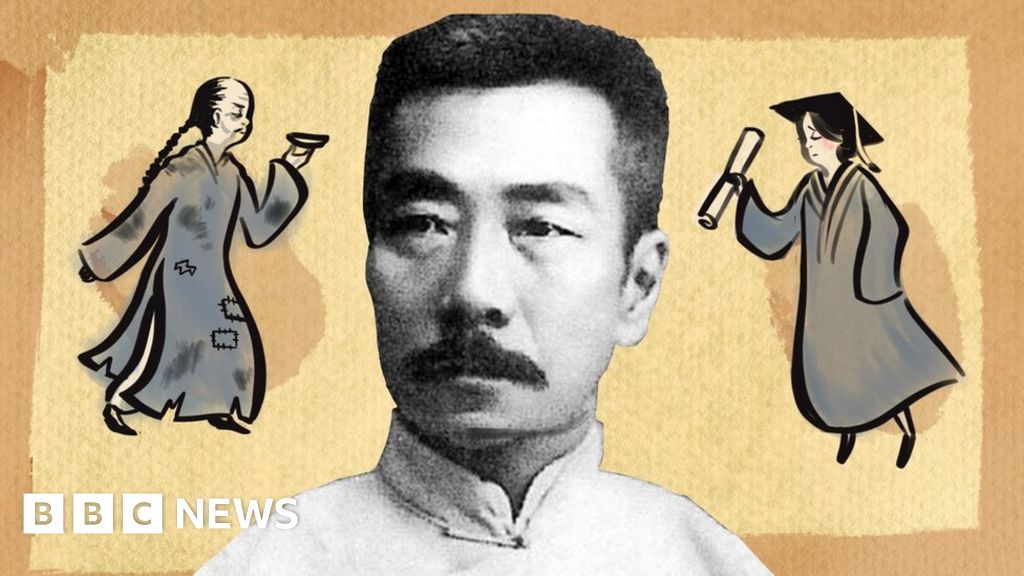

Getty ImagesTo appreciate how that paradox functions, consider Dürer’s famous meditation Melencolia I (1514), which might be said to have set the tradition in motion. In the influential woodcut print, a winged and lugubrious angel, head on fist, twiddles a pointless compass while all around her a jumble of seemingly irreconcilable symbols lie scattered. What does it all add up to, this straight edge and hammer; those pincers and scales; that ladder and tongs; the censer and sundial? How are we to measure the metaphysical heft of this hulking polyhedron that squats in the middle-ground of the work? Is that a skull grimacing in the stippled pixellation of its multidimensional face?

What, moreover, are we to make of the pudgy cherub (or putto) who, with sightless eyes, scribbles onto a blank slate, while perched on top of a discarded grindstone in the centre of the engraving? Is that a rainbow we see behind him in the distance? And below it, a comet? What exactly do all of these dramatic atmospherics have to do with the theme of ‘Melencolia’, as proudly proclaimed by the banner that the snarling bat unfurls in the sky? In Dürer’s day, melancholy was thought to be caused by an internal imbalance – an excess of ‘black bile’ (one of the four mysterious ‘humours’ believed, since antiquity, to determine one’s disposition) – and was linked with autumn and the planet Saturn. How are we to factor those variables into the already overflowing formula of insoluble clues?

Ever since Dürer created his vexing woodcut half a millennium ago, scholars have scratched their heads attempting to cram the myriad emblems, allegories, and tropes into a coherent narrative. With no single interpretation as yet proving conclusive, you wonder if the very irresolvability of the work is not its point and purpose. Rather than offering an emotionally direct depiction of melancholic despair, the engraving appears to provide instead a kind of cunning coping mechanism in the shape of an intractable puzzle – a kind of cognitive Rubik’s cube that takes our minds off our melancholy by utterly indulging it.

![Getty Images According to the philosopher Alain de Botton, melancholy is “not a disorder that needs to be cured, [but a] dispassionate acknowledgement of how much agony we… travel through”](https://unmenofvalormag.com/wp-content/uploads/2025/02/p07t7nkp.jpg.webp.webp) Getty Images

Getty ImagesIn the upper right-hand corner of the work, the mathematical miracle of a ‘magic square’ may be key to understanding how the work functions as a fidget spinner for psyches overwhelmed by life. A table of numbers in which the sum of every row, column, and diagonal is the same (in this case, they all add up to 34), Dürer’s magic square is the earliest known example of such an arithmetical wonder ever to be printed in Europe. The ingenious numerical grid (which includes, in the bottom row, the year the woodcut was made) invests the work with a sense of the universe’s inherent order and infallible logic, if only one can deduce what that logic is. Surrounded by symbols of mortality – the bell above it (a conventional metaphor for death) and the hourglass to its left (which measures the steady elapse of life) – the grid entices our eyes to search for the patterns and hidden harmonies that underwrite our existence, thereby coaxing us out of our ennui.

Alamy

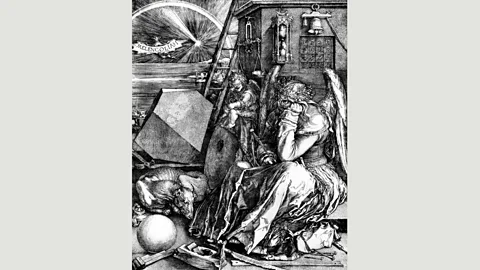

AlamyIt didn’t take long for the mystique of Dürer’s absorbing engraving to seep deep into cultural consciousness. For his oil-on-panel painting Melancholy (1532), Dürer’s contemporary, Lucas Cranach the Elder, recasts in the crispest of German Renaissance colours many of the same elements we find in the earlier black-and-white woodcut: a broody angel; a skinny dog; implements of woodworking; and the curious antics of a chubby child who, in Cranach’s take, has become a scrum of toddling triplets. Also on loan from Dürer’s print is the presence of a large blank sphere. What truly transfixes the eye, however, is the hoop held nearby by one of the putti, who are determined to nudge the sphere through the ring. But will it fit? Preoccupied by the likely success or failure of the infants’ task, we find ourselves, like Dürer’s own earlier angel, spinning our mental compasses, engrossed in the diversionary calculations of the relative proportions of the ball and ring – life and the wisdom of its ambitions. Lost in thought, we hardly notice that our melancholic moping has slowly alchemised itself into something more ennobling: philosophy.

Alamy

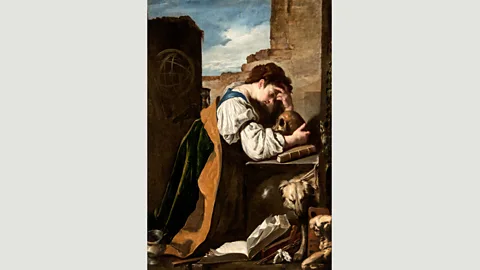

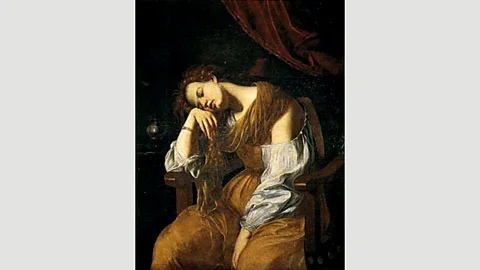

AlamyThe ensuing centuries witnessed a steady stream of reinventions of Dürer’s riveting design. Notable instances in the 17th Century, including paintings by the Italian Baroque artists Domenico Fetti and Artemisia Gentileschi, reveal a growing tendency to perceive melancholy as a privileged affliction associated with artistic genius. In Fetti’s Melancolia (1619), the by-now stock components of a dog and sphere, imported from Dürer and Cranach’s works, are accompanied by a clutch of paintbrushes (in the bottom centre of the painting) tied with a rag, and beside it, a small sculpture’s anatomical model. In Mary Magdalene as Melancholy, Gentileschi takes a different tack by bravely stripping away almost every symbolic object we’re accustomed to sifting through in the works by Dürer, Cranach, and Fetti, forcing us to focus instead entirely on the personification of melancholy, who just so happens to be a self-portrait of the artist herself. Here, the puzzle to be unravelled isn’t a rattlebag of random clues, but a palimpsest of entangled personality that Gentileschi has squeezed into a single subject, as issues of allegory, religion, and self-reflection are woven into one.

Alamy

AlamyBy paring back the clutter of emblems and allegories that clamour for our attention in earlier studies of chronic despondency, Gentileschi allows the human face and physique, in all their impenetrable poignancies and depths, to become the puzzle we worry over – and to assume the central focus of our melancholic wonder. Subsequent milestones in the tradition by Francisco Goya, Vincent van Gogh, and Edvard Munch, will learn from Gentileschi’s confident economy of composition.

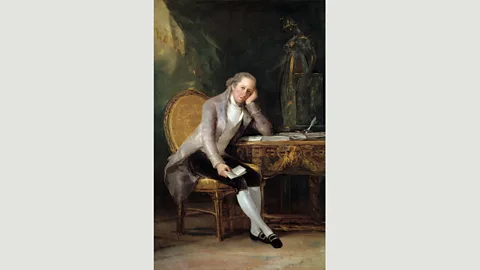

Alamy

AlamyIn Goya’s 1798 portrait of the Spanish Enlightenment statesman and man of letters, Gaspar Melchor de Jovellanos, it is a reverberating sadness in his stare that holds ours, not a contrived bundle of similes and metaphors. Any intellectual curiosity we might otherwise have had in the symbolic significance of the objects that surround Goya’s dispirited patron – the folded missive that weighs his hand down, say, or the uncanny compassion of the statue that extends a comforting hand towards his head – is superseded by the more immediate riddle of the subject’s suffering soul.

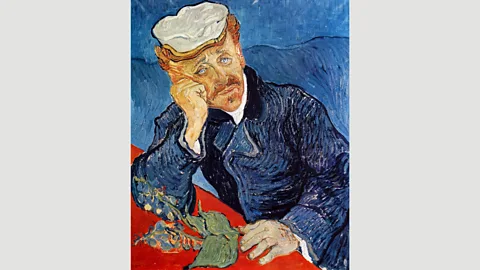

Getty Images

Getty ImagesBy the time we reach the heavy, hand-propped heads of Van Gogh’s likeness of his troubled physician Dr Paul Gachet, painted in 1890, and Munch’s own archetypal portrayal of depression, Melancholy (1891), it is clear that a profound shift in artistic attitude and aesthetic strategy has occurred, from over-analysed allegories (in Dürer, Cranach, and Fetti) to brash brushstrokes that captivate us more with the intensity of their passion than with the ingenuity of their intellectual iconography. Though the spaces that these forlorn figures inhabit in Van Gogh’s and Munch’s works are no longer the claustrophobic and carefully calibrated engines of emblem and metaphor we encountered centuries earlier, they are no less diverting in their lyrical allure.

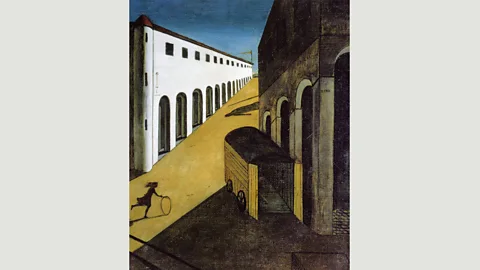

The same can be said for De Chirico’s dreamy ode to desolation, Melancholy and Mystery of the Street, which paradoxically seeks to lead us out of loneliness by trapping us inside it. Here, a girl rolling a hoop that she appears to have prised loose from Cranach’s cryptic painting, spins her way towards the cold light of an abandoned square as the lengthening shadows cast by an unknown future stretch ominously towards her.

Alamy

AlamyGone altogether is the central seated subject, weary from worry, whose languid posture has reliably defined old master depictions of despair until now. With no face or physiognomy to psychoanalyse and no scatter of ambiguous objects to decipher, our eyes are left to contemplate instead the unsettling misalignment of diverging perspective lines and vanishing points that dislocate the scene into an eerie elsewhere – a realm physically and psychologically disjoined from time and space, yet strangely familiar.

From Dürer to De Chirico, artists have perennially sought to seduce us out of sadness with ever-evolving visual gadgetry. But what happens when the source of our melancholy threatens not merely to consume our own peace of mind, but everyone and everything? In April 2019, at a site near Marble Arch in London that had been occupied by activists demanding action to combat climate change, a mural appeared overnight that audaciously escalated the imagery of melancholy, taking the tradition to another level.

Getty Images

Getty ImagesThe graffitied work, widely attributed to the street artist Banksy, depicts a child kneeling beside a small spade and the fragile reach of a fledgling sprig she’s just planted. She holds in her hand a tiny placard imprinted with the memorable geometric logo of the non-violent environmental movement Extinction Rebellion: a stylised hourglass encompassed by a sphere, echoing elements from Dürer’s seminal engraving. Emblazoned in the concrete air next to the stencilled girl is the stirring spray-painted phrase ‘from here despair ends and tactics begin’, which could as easily have described the artistic strategies of any of the foregoing paintings by Cranach and Fetti, Gentileschi and Van Gogh, Munch and De Chirico. The explicitness of the mural’s message betrays its urgency. There’s no longer time to muse over hidden meanings or decrypt the entangled connotations of secret symbols. The age of subtlety is over, the mural seems to say. Melancholy is a luxury our survival cannot afford.

Source link